Articles

Welcome to our blog! This is where we share policy/regulatory recaps, blockchain developments, and more exciting updates.

Why Fungible Crypto Assets Are NOT Securities

Why fungible crypto assets are not securities The speakers at our Owl Explains Hootenanny last week are co-authors of the most thorough analysis to date of the burning question of whether fungible crypto assets are - or are not - securities. (Spoiler alert – mostly they are not.) Lewis Cohen, Freeman Lewin and Sarah Chen from DLX law firm have analysed the US Securities Acts, the ‘Howey test’ on investment contracts (more on that below) and 266 pieces of case law where the Howey test was applied to different scenarios. The resulting paper is 180 pages long. But fear not! This owl has served up this pithy appetizer to whet your appetite for the full feast which you can find here. So what’s this all about? The flurry of Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) a few years ago has led some regulators to conflate the token sales in an ICO and the crypto assets involved in them and seek to apply US securities laws to both. The authors of this paper do not dispute that the fundraising activity of an ICO – inviting investors to purchase crypto assets in a fledgling project with the hope of making a profit – might indeed involve an investment contract and that securities law would often apply. What they dispute is whether and when the crypto assets themselves qualify as ‘securities’ according to current laws and regulations. Just as oranges, chinchillas, whiskey barrels and stamps can form part of an investment contract but are not themselves securities, the same goes for crypto assets. (This owl particularly enjoyed the bit about how chinchillas are not securities – of course they aren’t – they’re lunch). They also challenge the notion that ‘once a security, always a security’ that continues to classify a crypto asset as a security well beyond the context of an ICO when the crypto asset may be performing all manner of other functions that do not involve an investment contract. So what should regulators do instead? The co-authors recommend that the status of a crypto asset can only be determined by first understanding the true nature of the crypto asset – and then by understanding and applying case law and legal scholarship on investment contract transactions. And that is exactly what the article does – exploring first the nature of crypto assets and then delving into case law and legal scholarship to explore when an investment contract does and does not exist. Why does this matter? It matters more than ever right now as policy makers and regulators, particularly in the US, are leaning towards deeming many, even all, crypto assets to be securities without going through this exercise of interrogating the nature of the asset and the transaction. And that matters because if all crypto assets are treated as securities even if they represent things that clearly are not – and even when they are clearly not part of an investment contract - regulators risk not only strangling with red tape the innovation and promise of Web3, but also causing confusion for all manner of items like the aforementioned chinchillas. So when is a crypto asset a security? A crypto asset is a security either by its very nature (e.g., a stock or bond on blockchain). When it is part of an investment contract according to the Howey Test, well, the crypto asset is not a security but the investment contract is. Clearly crypto assets cannot be assumed to be securities by their very nature – because a crypto asset can represent literally anything at all. They may occasionally be – but equally (and more often) they may not be. So where the asset is not a security by nature, we have to assess whether they might be part of an investment contract as defined by the Howey Test. Still not a security, but the subject of an investment contract. So what is the Howey Test? The Howey test says that an investment contract transaction exists when a “contract, transaction or scheme” involves an investment of money in a common enterprise with an expectation of profits to come solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party. So the Howey test defines correctly that fundraising by selling crypto assets as part of an ICO might be an investment contract that the securities laws apply to. And while crypto assets are part of that investment contract, they are not themselves securities. But what happens when the fundraise is complete and the crypto assets are being used for other purposes where Howey tells us clearly there is no investment contract? An example could be when they are merely validated, delegated or staked. Or when they are performing as a utility token intrinsic to the functioning of a blockchain. The article does not shy away from the complexity of all this. In fact it opens with a quote from Homer’s The Odyssey where the old man of the sea changes himself ‘first into a lion with a great mane, then all of a sudden he became a dragon, a leopard, a wild boar; the next moment he was running water and then again directly he was a tree’ Why? Because crypto assets can also shape shift in that different circumstances can affect whether a crypto asset should be treated as a security or not. With this mercurial nature then, regulators and practitioners need to consider each and every transaction and activity concerning a crypto asset on a case by case basis to determine whether there is a security or not. But this isn’t always possible because the information needed to make that assessment is private. So what is the solution? A new law and more engagement from and between the SEC, FTC, CFTC, Department for Justice and state attorneys general. So you mean regulation? Yes. Fundamentally the co-authors call for regulation based on the kind of thorough understanding and legal analysis of crypto assets that this paper provides. Other resources Our wise owl Lee Schneider has written a few essays that talk about these issues and are available here and here.

What is a financial product?

Click the link below to download the PDF

FASB Delves Into Sensible Token Classification

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) is seeking feedback on its proposed treatment regarding the accounting for and disclosure of a narrow category of crypto assets. The proposed Accounting Standards Update (ASU) is intended to improve information provided to investors about a company’s crypto asset holdings. Comments are due June 6 and may be submitted through the website or emailing comments to director [at] fasb [dot] org, File Reference No. 2023-ED200. The ASU sets forth the accounting treatment for the class of crypto assets that meet the following criteria: Are intangible assets; Do not provide the asset holder with enforceable rights to, or claims on underlying goods, services, or other assets; Are created on or reside on a blockchain; Are secured through cryptography; Are fungible; and Are not created or issued by the reporting entity or its related parties. Sound familiar? This follows the principles discussed in the sensible token classification systemand in particular the class called “native DLT tokens”! The IRS also recently discussed token classification. See our note on the guidance release, available here. Owl Explains is elated by these developments because proper token classification is Branch 3 of our Tree of Web3 Wisdom. Under the ASU, reporting entities would need to measure at fair value changes in net income associated with this class of asset during each reporting period. Meanwhile, transaction costs related to acquiring this type of crypto asset, such as fees and commissions, would be recognized as an expense as incurred absent industry-specific guidance that the reporting entity capitalize those costs. The ASU would also require these crypto assets to be presented separately from other intangible assets (whether tokenized or traditionally represented) on a reporting entity’s balance sheet and changes in the fair market value of crypto assets would be separate from changes in the carrying amounts of other intangible assets in the income statement. Further, if this type of crypto assets are received as noncash consideration in the ordinary course of business and they are almost immediately converted into cash (i.e., as payment for goods and services), then the entity would be required to classify those cash receipts for goods and services paid in crypto assets as cash flows from operating activities. The ASU also lists the information that would need to be disclosed with respect to crypto asset holdings. Notably, based on these criteria, NFTs would likely be excluded from the ASU since NFTs often provide holders with certain rights to goods and services and they are not fungible, as opposed to fungible crypto assets that are used for general purposes on a blockchain.

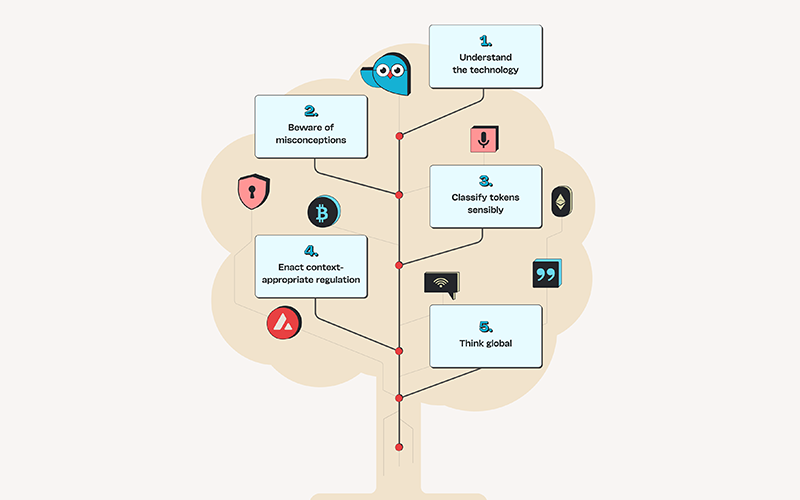

Introducing the Tree of Web3 Wisdom

Introducing the Tree of Web3 Wisdom - 5 branches to guide policymaker thinking The world of Web3 is rapidly evolving, while policymakers keep up with the latest developments to enact effective, sensible regulation that nurtures important technologies and protects consumers. This is a global phenomenon. Japan continues to update its first-in-the-world comprehensive cryptoasset regulation; Singapore regularly iterates on its regulatory regime, as does South Korea and many small Asian jurisdictions. The EU is on the cusp of implementing its Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA), while various US regulatory agencies continue the work assigned to them in the President’s Executive Order from March 2022. The US Congress is also hard at work with hearings and draft bills. Against this backdrop, the Tree of Web3 Wisdom provides a helpful framework for understanding the key aspects of Web3 technology and which first principles are important for regulating it. Let's explore the five branches of the Tree of Web3 Wisdom and their implications for policymakers. The first branch of the tree is to understand the technology. Before regulating Web3, it's essential to have a deep understanding of blockchain technology. Blockchain allows for digital ownership and transfer of value across the internet, with enhanced security, transparency, auditability, programmability, and scale. It also enables users to program on these databases to create applications that are part of a larger tech stack for anything their creativity can imagine. This technology has the potential to empower communities, remove friction, verify credentials, and create new efficiencies in commerce. It's essential for policymakers to understand the capabilities of blockchains and the problems they solve to see the potential benefits and risks involved in its implementation. The second branch of the tree is to beware of misconceptions. Blockchain technology isn't just about financial transactions. It's a new infrastructure for the internet, providing a decentralized system that promotes transparency and security by having no single point of failure, no single source of truth, and no single entity or authority with the power or obligation to change data or transactions. Crypto assets and blockchain are not synonymous. Blockchains facilitate crypto assets, but they also facilitate many other types of activities by allowing data integrity and digital uniqueness through tokenization. Crypto assets are a way to digitally represent something on a blockchain. Decentralized systems promote transparency and security by having no single point of failure, no single source of truth, and no single entity or authority with the power or obligation to change data or transactions. Decentralization does not necessarily mean "permissionless and public," and it is crucial to understand that blockchain technology can be permissioned and private too. DeFi is more than just trading financial instruments–it is an avenue to democratize commercial systems by using blockchains and smart contracts to replace traditional intermediaries with built-in trust mechanisms. NFTs are not just for collectibles and art with revenue streams. An NFT is a type of token that is digitally unique, allowing for more specialized representations regardless of the industry. The third branch of the tree is to classify tokens sensibly. A token is a digital representation of something on a blockchain, such as an asset, item, or bundle of rights. Tokenization allows the item's ownership to be established and transferred globally on one or more blockchain networks. A sensible classification systemrecognizes the nature of a token based on the item or rights it represents, whether it's a physical item, intangible item, a type of service, or simply a native token integral to the functioning of a particular blockchain network. Treating all tokens as financial instruments or the trading of tokens as financial activity will unnecessarily limit their use in commerce, communications, entertainment, recreation, governance, and anywhere else establishing ownership. It's essential to classify tokens sensibly to understand their utilization, valuation, and legal classification and, therefore, their appropriate regulatory treatment. The fourth branch of the tree is to enact context-appropriate regulation. Just like plants need specific care depending on their nature and location, blockchain and crypto require appropriate regulation based on their context. Responsible actors want sensible policies that incentivize growth and good behavior, punish bad actors, and regulate intermediaries. Appropriate laws and regulations traditionally have been determined according to the type of asset or technology and its context, i.e., how it is being used, by whom, and the associated risks. This same approach should apply to blockchains and tokenization, which are just a new way of establishing ownership and transferring value. It's important to note that innovative programs and features on a blockchain are run by autonomously-functioning code, and their role needs to be carefully considered when regulating. In enacting context-appropriate regulation, policymakers must also consider the impact of blockchain and crypto on individuals and society. Finally, the fifth branch of the tree is to think global. This last branch of the Tree of Web3 Wisdom emphasizes the ongoing evolution of blockchain technology and the endless possibilities for its use in various fields. The potential applications of blockchain technology go beyond financial transactions and encompass a wide range of industries, such as healthcare, supply chain management, voting, and identity verification. Just like the internet, blockchains and crypto assets are global and require a coordinated regulatory approach based on certain "first principles," including disclosure, market integrity, disclosure, anti-fraud, privacy, and operational integrity. As blockchain technology continues to mature and evolve, it will likely provide even more benefits, such as greater privacy, scalability, and interoperability. Quality builders, including developers, entrepreneurs, and investors, will play a crucial role in driving innovation and creating new and exciting ways to use blockchain technology. Just look at Lemonade Foundation, as one example. However, this ongoing innovation and growth also requires sensible regulation to strike a balance between fostering innovation and protecting consumers and the broader economy. In conclusion, the Tree of Web3 Wisdom provides policymakers with five critical principles to guide their thinking when considering how to regulate blockchain, tokenization, and Web3. By understanding the technology, avoiding misconceptions, classifying tokens sensibly, enacting context-appropriate regulation, and thinking globally, policymakers can create a regulatory framework that fosters innovation while supporting safety and security for all stakeholders. Read the Tree of Wisdom in full here.

OCC Symposium Explores Tokenization of Real-World Assets and Liabilities

In February 2024, the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) hosted its Symposium on the Tokenization of Real-World Assets and Liabilities. The OCC is one of three prudential banking regulators in the United States, overseeing national banks and federal savings associations. Its role in ensuring the safety, soundness, and fairness of the banking system means it is imperative for the regulator to assess how the entities it supervises are planning to leverage distributed ledger technology (DLT) to provide new and enhance existing products and services. The tokenization of real-world assets and liabilities, such as commercial deposits, real estate, commodities, or art, involves converting the ownership rights of these assets and expressing them as digital tokens that can be traced on DLT. This process has the potential to revolutionize the way assets are bought, sold, and managed, offering increased liquidity, transparency, and accessibility. However, it also presents new regulatory queries, particularly in terms of ensuring compliance with existing financial regulations, safeguarding against money laundering and fraud, and protecting investor rights. As tokenization of real-world assets and liabilities becomes further integrated in the financial system, the OCC's role and regulations will likely influence how other regulatory bodies, both domestically and internationally, approach tokenized assets’ oversight. Importantly, and excitingly, many of the themes discussed during the event fall under the five branches of the Tree of Web3 Wisdom. The Tokenization Symposium began with remarks from Acting Comptroller Michael Hsu, where he defined tokenization as “process of digitally representing an asset’s liability, ownership, or both, on a programmable platform,” and called on event attendees to understand the technology. He set as the “north star” for the event, identifying problems and proposing solutions accordingly, as opposed to developing solutions in search of a problem. Panel 1: Legal Foundations for Digital Asset Tokens consisted of members of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) drafting committee and others who were supportive of the UCC, a comprehensive set of laws governing commercial transactions in the United States, including sales, leases, negotiable instruments, and secured transactions. The panel argued that amending the UCC to include digital assets benefits token holders because it provides statutory protection compared to enforcing rights through suing over contract rights, and this is particularly important in situations such as bankruptcy, where there is a legal process for asserting claims to recover funds. The panel discussed how the United States has the most advanced body of rules for commercial law, given efforts to amend the UCC to recognize use of DLT, as opposed to other jurisdictions where the common law is still developing. During the discussion, the panelists discussed how it is important to take into consideration the sensible classification of tokens, comparing the concept of tokenization to using paper as a medium for recording rights and liabilities. Panel 2: Academic Papers on Tokenization explored three academic papers: 1) how the acceptance and usage of digital payments leads to increased financial inclusion; 2) the use of payment stablecoins for real-time gross settlement; and 3) a study on the economics of NFTs. The panelists in their presentations discussed thinking globally with respect to how tokenization is occurring across the world and how it can facilitate cross-border payments and support financial inclusion objectives. Panel 3: Regulator Panel featured staff of the innovation offices from the OCC, Federal Reserve (the Fed), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Each office discussed how they are seeing tokenization of real-world assets and how they interact with other aspects of DLT such as smart contracts. The regulators discussed opportunities for tokenization within the banking sector, such as tokenization of deposits, tokenized money market fund shares, and the benefits they can provide in areas such as correspondent banking, repo transactions, and post-trade processes. One area they flagged as an opportunity is increasing the accuracy of systems under the Bank Secrecy Act to monitor for money laundering, terrorist financing, and sanctions screening more efficiently. Interoperability is one challenge they are seeing with respect to tokenization. The panelists discussed throughout how regulation of digital assets should be context-appropriate. Panel 4: Tokenization Use Cases featured representatives from the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC), Mastercard, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The panelists discussed exciting use cases that tokenization and DLT are enabling such as T+1 settlement and tokenization for private markets, multi-rail payments that support complex types of payments that enable increased coordination, reduce counterparty risk, and enable greater fraud controls. The panelists also touched on how policymakers and innovators should beware of misconceptions when assessing the various use cases. Some themes that echoed from previous panels included challenges around interoperability, developing solutions based on need, and carefully developing regulations based on the use cases. Panel 5: Risk Management and Control Considerations also explored various tokenization use cases and areas where tokenization can make a big difference, such as markets where capital is freed up and markets become more liquid. The panelists discussed the perspective regulators should use when approaching risk management and developing standards to minimize risk. They also discussed the role of intermediaries in tokenization and how industries have evolved and become more "dis-intermediated" over time. In their closing statements, the panelists called for regulators and policymakers to understand the technology and experiment more with it to better understand its implications. The Symposium ended with a keynote speech featuring Hyun Song Shin (Economic Advisor and Head of Research at the Bank for International Settlements) regarding how tokenization can help propel innovations in the monetary system similar to money and paper ledgers. He discussed various concepts involving tokenization such as improved delivery versus payment, central bank digital currency, the “singleness of money” with respect to tokenized deposits and stablecoins, and the "tokenisation continuum" that maps out different use cases ranging from wholesale payments to land registries. In conclusion, the OCC Symposium on the Tokenization of Real-World Assets and Liabilities underscored the need for careful consideration, collaboration, and continuous innovation. The diverse perspectives shared across legal foundations, academic research, regulatory insights, use cases, and risk management considerations have collectively woven a narrative of both promise and challenge. Moving forward, it is clear that embracing the digital evolution calls for a harmonious blend of regulatory adaptability, technological exploration, and a shared commitment to understanding the profound impact tokenization can have on the global financial ecosystem.